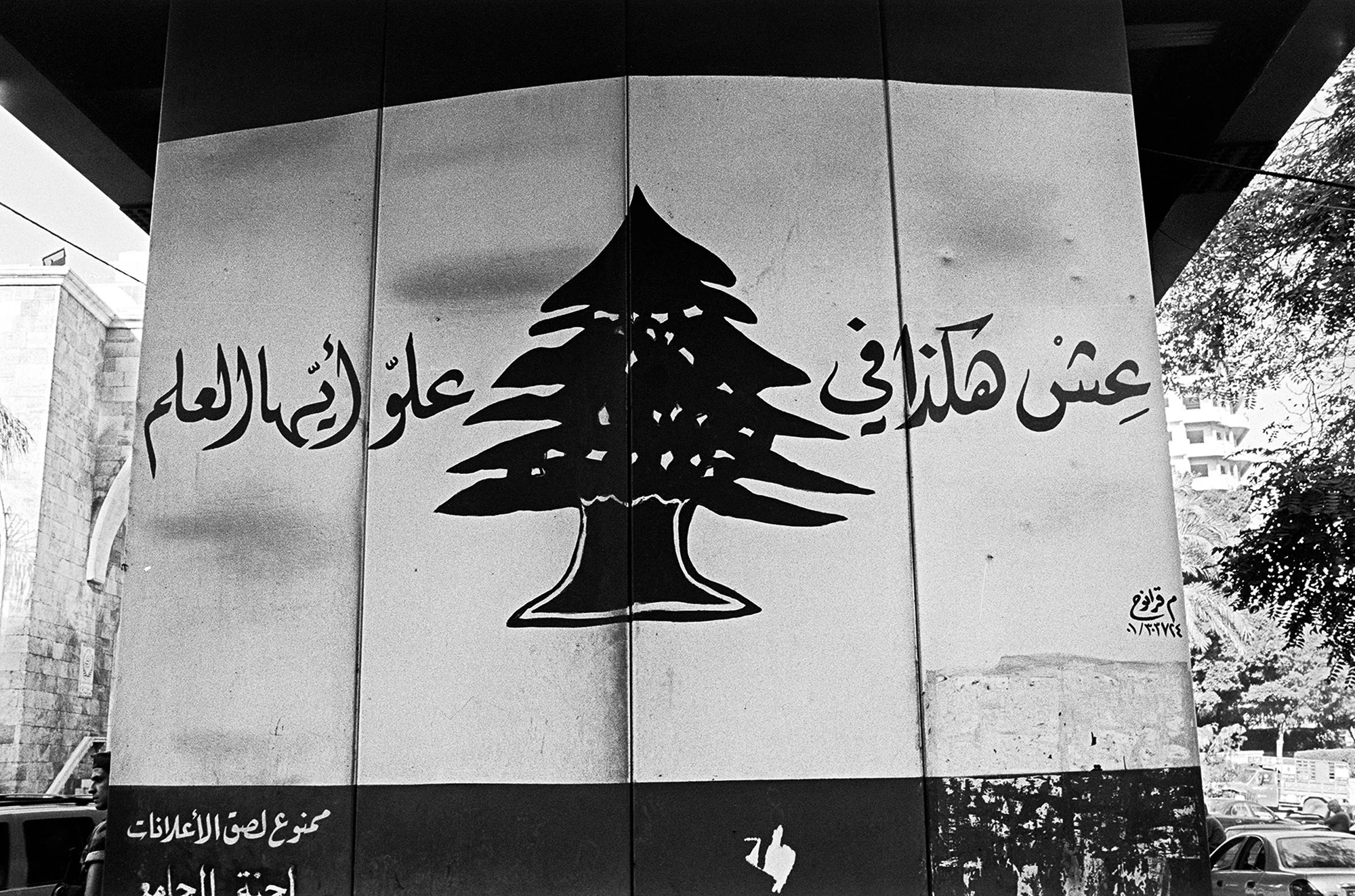

LEBANON

THEY WILL CURSE US

Forty-two-year-old Amal sits on the couch while her husband Bilal (46) sits on the tiled floor of their small 3-room home on the outskirts of Beirut. Their daughter, Rana (7) and son, Rafiq (3) sit quietly on another small couch a few feet away.

“We fell in love and got married,” Amal describes. “We thought we had hoped to live. We hired a lawyer and thought there was a solution to our problem. I thought we could have kids, start a home and live happily. I could not pass on citizenship to my husband. And I am native Lebanese from a Lebanese father and cannot do anything for my children. I cannot pass on citizenship or anything else to make them happy.”

Married in 2004, the couple had already been together for fifteen years. When they decided to marry, Amal’s parents strongly opposed the decision. How could their daughter marry a stateless man? How could she marry someone with no documents; someone, who even though he was born in Lebanon and had lived his entire life in Lebanon, could not prove he was Lebanese? Someone, who in their eyes, would ruin the picture they had for the future of their daughter? But they married anyway. “We have not seen a good day since,” Bilal explains.

Amal is still technically single according to her documents. In the eyes of the religious courts in Lebanon, they are married, but with Bilal being stateless and without documents, the Lebanese state would not legally recognize their marriage. After they married, Amal believed that as a Lebanese citizen whose family had lived in Lebanon well before Lebanon was even a country, the law would help empower her to secure Lebanese citizenship for her husband and that this would also provide Bilal with the legal affirmation he had always desired in the country of his birth and the country of his father’s birth. She also believed that in doing so they could rightfully be man and wife. But the laws failed them and the laws would fail their children as well.

When their daughter Rana was born in 2005, it made no sense to Amal to be told that she, a Lebanese woman and citizen, could not pass her citizenship on to her child. She was told the same thing when they had their second child, son Rafiq a few years later. Since then Amal has spent her days consumed not only with trying to find much needed healthcare for Bilal, who suffers from severe diabetes and is now unable to work as a result of his disabilities, but also with trying to navigate her way through the complex bureaucracy of Lebanese politics in an effort to find a way to pass on her citizenship to her husband and children. She has sought legal assistance, but it has been impossible to penetrate Lebanon’s archaic nationality laws. All her efforts have been fruitless. Bilal continues to be stateless, and Rana and Rafiq have both inherited his statelesness as well, unable to receive citizenship from their Lebanese mother. “Our children are going to grow up and curse us for the situation they are in,” Amal says.

"Why in any other country in the world can mothers pass on citizenship? Why as mothers, can we not? Don’t they appreciate a mother’s heart? Her feeling towards her children? Every mother in the world wants their children to be the best among people."

Twenty-seven countries in the world, including Lebanon, possess citizenship laws that do not permit women from passing their citizenship to their husbands or their children. Lebanon has been one of very few countries in the region with a history of progressive policies related to the equal rights of women. Yet, the inability for a Lebanese woman to pass on her citizenship is seen by many women and rights groups as a gross violation of a fundamental right that in many ways thwarts the progress the country has made related to the ‘equality’ of women in Lebanese society.

Lebanese nationality laws in existence today are largely based on laws that were implemented in 1925 while Lebanon was still under the mandate of French colonial rule. Originally a territory consisting predominantly of Maronite Christians, France’s expansion of Mount Lebanon in 1920 with four surrounding and predominantly Muslim regions to form Greater Lebanon created a religious and political imbalance that threatened the Christian-elite a the time.

Lebanon’s first constitution in 1926 implemented a system governed along sectarian lines where political representation and power would be proportional according to religious demographics, which recognized seventeen groups based on confession. As a result, the criteria and mechanisms in which Lebanese nationality were defined or acquired in the years leading up to the 1932 census would be manipulated and exploited to unnaturally tilt the religious makeup of Lebanon for political purposes. Even after Lebanon’s independence in 1943, the results of the 1932 census would solidify the country’s political structure and embolden the legitimacy of Christian-dominated government in Lebanon for nearly forty years until civil war broke out in 1970.

Eventhough political power after the end of the civil war in 1990 would be shared evenly 50:50 between Christians and Muslims, the true demographic makeup of the country remains unconfirmed because the 1932 census eighty years ago was the last official census conduced by subsequent Lebanese governments. But seventy years has passed since the last census and the demographic makeup of Lebanon has seen any number of influences since then.

"It Is a problem that I hide more than I show. somehow it makes you feel of less importance or of less value. it immobilizes you. in life, You are stuck in one place."

"For me, it is already done. Maybe I would have gone to school and found a proper job. But for me it is done. Now the problem is for my children."

Even today, and to the detriment of an estimated 80,000 stateless people in Lebanon (not including the Palestinian community), interests along confessional lines rest at the core of the DNA makeup of Lebanese politics. If laws were changed and mothers were permitted to pass Lebanese citizenship to their children, tens of thousands of children, including thousands of children born to Palestinian fathers, would become Lebanese citizens. So for decades, the disruption of the country’s fragile demographic balance, however inaccurate or artificial it might be, has been used as justification for maintaining the status quo.

Thirty-year-old Rola, whose mother is a Lebanese national and father is Palestinian, agrees. Rola was born in Bekaa Valley in 1982. Her grandfather left Palestine in 1948. Her father was born in Lebanon and eventually married a Lebanese woman.

“The excuses are that they don’t want to affect the religious balance of the State’s political system. And because of things as women granting nationality to their foreign kids might affect the country’s sectarian system and create a demographic imbalance.” Rola says.

“In my point of view these are really meaningless excuses because first of all, the Lebanese woman is diminished. She’s not seen as equal to man in nationality issues. And second of all, it underestimates Lebanese women because of her being a woman, not because she is a Lebanese woman, but because she belongs to the female gender. And here the segregation is based on gender.

“It underestimates her ability to choose a companion and to make her own decisions such as who is going to be her husband. Is he going to be Lebanese or not? From the same sect or not? And here you see how we are fighting against minds. Minds who see women as lower than them, and minds who only care about the power of religious groups in this country and which the religious balance is based upon the power of religious groups and the division of high positions is based upon as well.”