Malaysia

HELD IN THE SHADOW OF THE SUNRISE

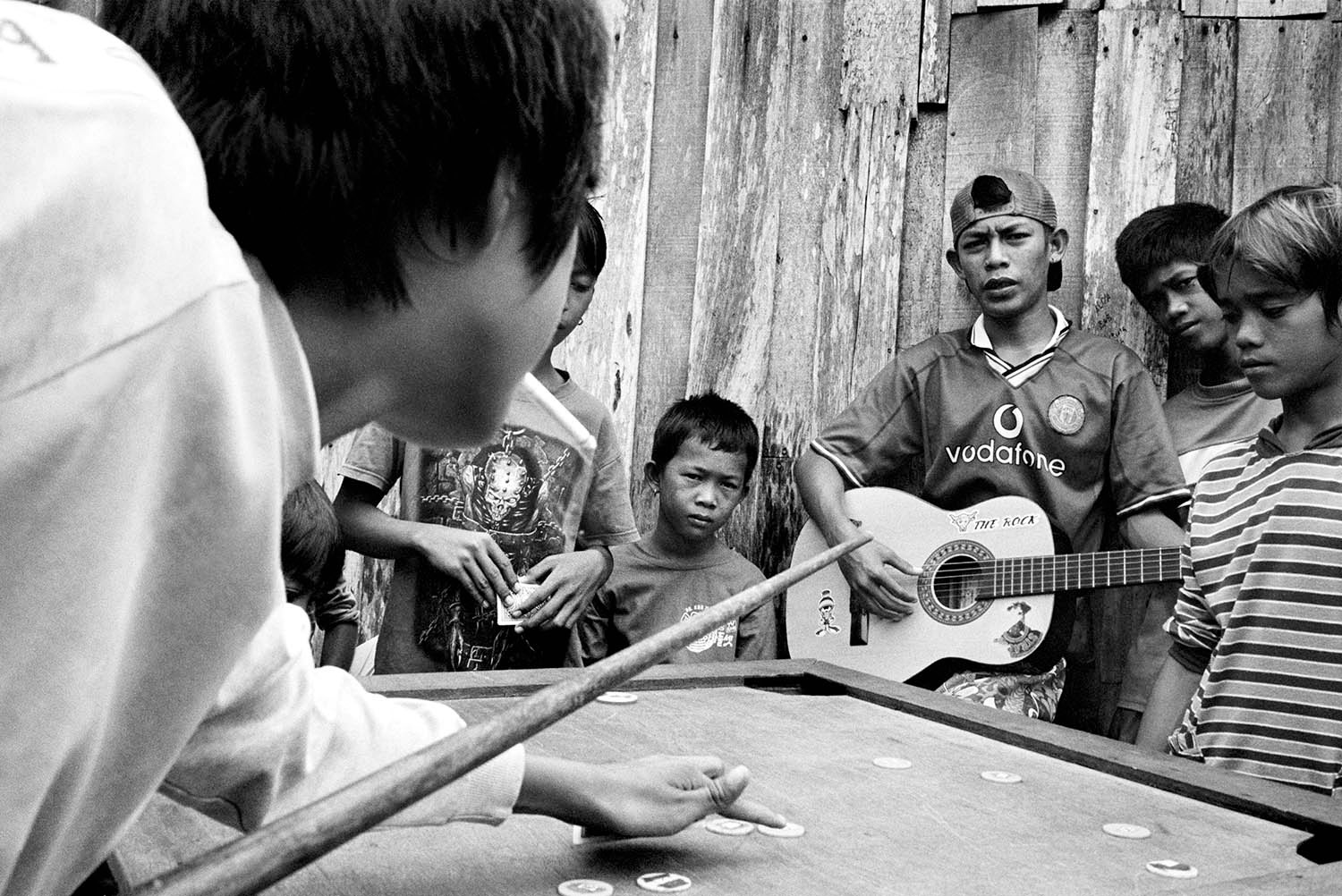

As the heat and humidity climb, life slows to a crawl in the port town of Kota Kinabalu. It has been a few hours since work came to a close for fourteen-year-old Davith and his four friends. It was a busy day in the fish market. A steady stream of boats brought loads of cargo to market that morning and there was no shortage of customers needing help transporting their purchases. Work started around six thirty and finished by eleven. Hidden among the boxes and empty stalls of a produce market, the boys lay around in the shadows talking and poking fun at each other, pausing occasionally to hold limp plastic bags up to their faces and huff glue. All four were born in Malaysia to parents originally from the Philippines. None of them have birth certificates or other forms of documentation, and none have been to school. Most of their parents had been arrested and deported back to the Philippines, leaving behind each child to fend for himself—undocumented, stateless, homeless and alone. The boys met on the streets and looked out for each other the best they could. Now for these few hours, Davith and his friends seek the comfort of shade. Eventually, they drift off to sleep with hazy heads, only to wake later in the day, slip on their flip-flops and work the streets in the evening, selling cigarettes or lottery cards. They are just a few of the estimated fifty thousand stateless children across Sabah.

Today, over three million people reside in the state of Sabah in Malaysian Borneo. Nearly one third are people who legally or illegally migrated to Malaysia over the past forty years, mainly from Indonesia and the Philippines. Civil war under President Marcos in the Philippines sent a stream of refugees to Sabah throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In addition, the demand for cheap labor on Sabah’s timber and palm oil plantations attracted thousands of migrants into the state. Although the industries driving Sabah’s economy depend on migrant labor to survive, strict immigration and citizenship policies have been implemented to preserve the interests of Malaysians and curtail any influence this immigrant community might have, if extended equal rights.

Foreign migrants working legally in Malaysia are not permitted to marry or have children while in the country. Marriages must be legally recognized by the migrants’ foreign governments. As there is no Filipino consulate in Sabah, most Filipino migrants cannot obtain marriage documents. Irregular migrant parents often do not possess documents themselves, which Malaysian authorities require to issue a birth certificate for any child born in the country. Many who live in remote areas cannot afford to travel to the cities where consulates can be found, and are frequently not even aware of the procedures. Migrant women who are found to be pregnant while employed in Malaysia risk immediate deportation.

For the thousands of undocumented people living and working in the country, the fear of exposing their presence to authorities influences their decision of whether or not to give birth in a hospital. As a result, large numbers of children born in Sabah do not receive birth certificates and documentation and are shut out from accessing public schools and affordable healthcare. Moreover, they are destined to wear the stigma of “foreigner” for the rest of their lives.

Locals have grown more intolerant of foreigners in the state. Regardless of how long the migrants, refugees and their families have been in Sabah, locals feel they compete for jobs and introduce unwanted social strains and ills into Sabah society. In recent years, Malaysia has stepped up efforts to control and reduce the number of undocumented people in the country. Special immigration task forces regularly conduct raids, which result in the arrest and deportation of thousands of people each year, frequently separating families.

The situation has generated heated debate and has seen the immigrant community blamed for any number of larger issues. Families from these communities have now lived in Sabah for decades. Tens of thousands of children and young adults have been born in Sabah, grew up in Sabah and possess no connection to the birthplace of their parents or grandparents, yet continue to be forced into the shadows of the only home they know.

On the opposite side of Sabah, 350 children sit together in a building in a remote industrial area outside the town of Sandakan. They carry small book bags and are well-behaved. They share benches arranged in rows and listen to the headmaster of their informal school talk before dismissing them to smaller classrooms. A picture of a strawberry, an apple, a cherry and other pieces of fruit are drawn on a blackboard in a small classroom with the corresponding English words below. A seven-year-old enters the classroom. She walks over to the blackboard and looks at the drawings. Several other classmates follow her. They chat for a few seconds, then find their places at wooden tables and wait until their teacher begins their vocabulary lesson. Though most of the children here at this makeshift school have a place to live and families to take care of them, like Davith, they have been born to foreign migrants. “Almost all of them are stateless,” says their teacher. Minutes later, class begins.