Nepal

STRANDED IN THE MIDDLE GROUND

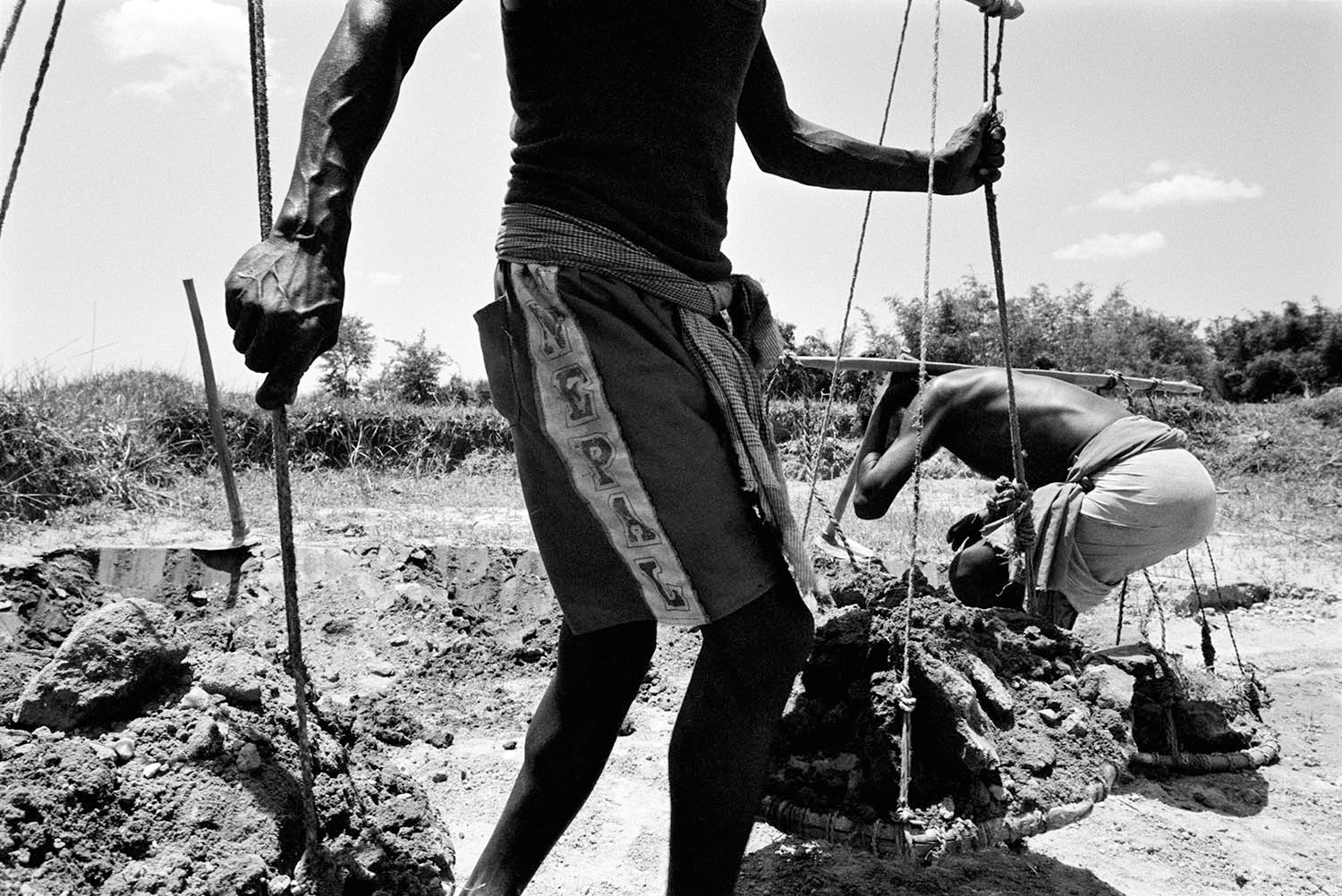

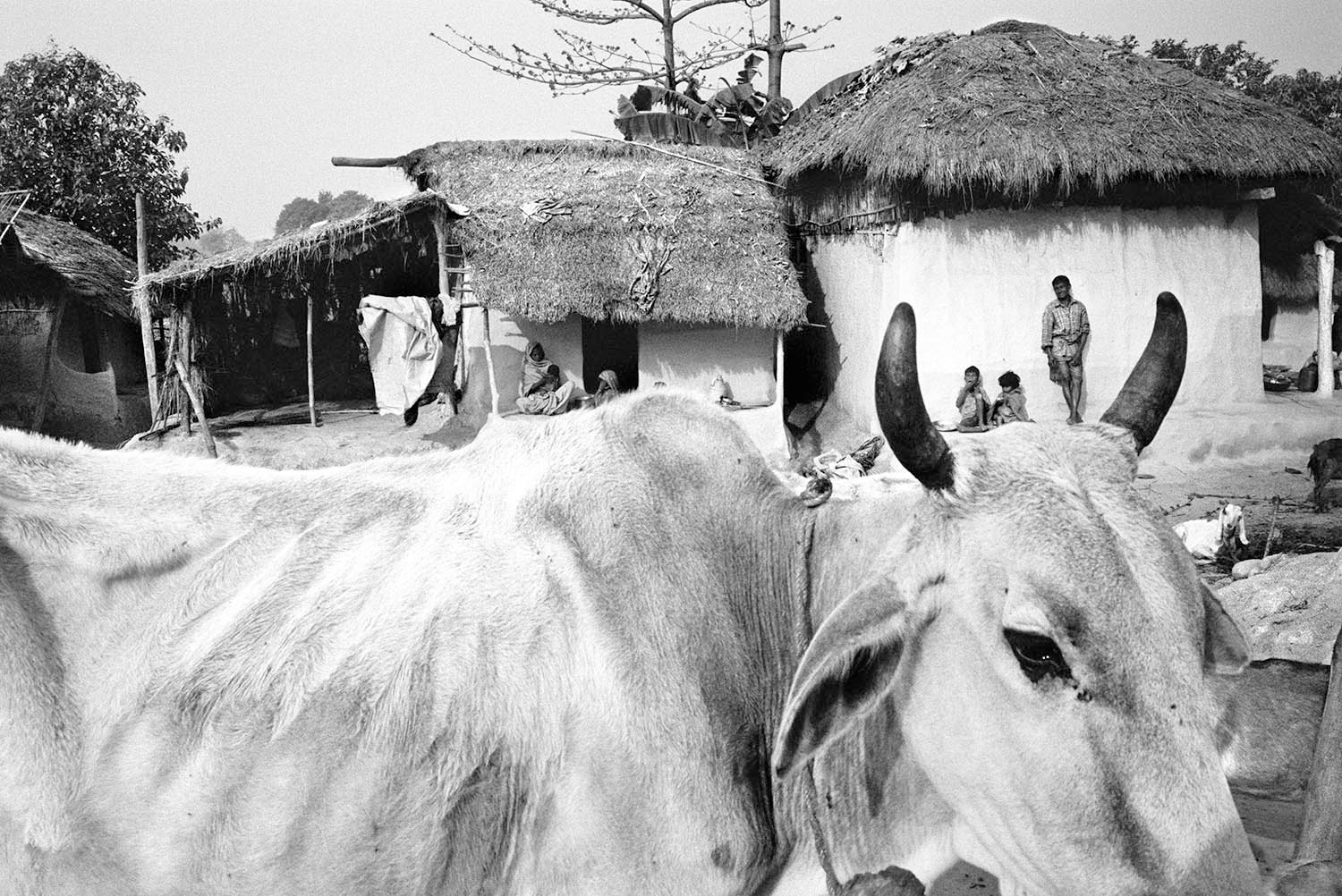

Each night during the winter months, a thick fog sweeps over the lowland plains of the Terai in southern Nepal along the border with India. In the early hours, the slow sunrise burns away the thick mist and reveals silhouettes moving around the open fields. Carrying wood, tilling soil, slowly pedaling a squeaky bicycle, walking with quiet grace; the silhouettes are unidentifiable, yet connected and intertwined with the natural rhythms of the environment around them.

On this morning, thirty-eight-year-old Bhoje has already cycled for several hours, hauling wood from deep in the forest to sell in the dusty town of Lahan. As both a Dalit, born into the lowest of castes, and an inhabitant of the Terai, he faces a double burden of discrimination. All of the excitement over a more democratic Nepal has not improved Bohje’s life. He and most of the Dalit in his small village still lack Nepalese citizenship. Bhoje has rich eyes and a strong heart but, like most Dalit in the Terai, his life is smothered by poverty. He cannot own or develop the land he and his ancestors have lived and worked on for generations. Landless and stateless, he cannot seek work abroad and remit money back to his family and village as so many other Nepalese do each year. “How can I spend my entire life and how can I grow up as a child in Nepal, and not be from Nepal?” he says. “If I want to go out of the country, the government demands I have citizenship and a passport, but without citizenship, I can’t. I am a poor man and I am landless. For this I am fighting the government.”

Nepal’s coat of arms embodies equality, harmony and unity. The diverse regions of the country—blue mountains, green hills, golden plains—form a backdrop for the joined hands of a man and woman. A wreath made of crimson rhododendrons and grains of rice encircles a silhouette of the country. Yet, the dynamics within the country have been more conflicted and contradictory. Nepal consists primarily of two ethnic identities: Nepali-speakers from the Hills and non-Nepali speakers from the Plains. Each has played a different role in shaping the state of Nepal, yet only one has dominated. While nearly half of Nepal’s twenty-nine million people live in the Terai, they have historically been treated as outsiders by those from the hills and Kathmandu Valley who hold power in the country.

"There is a saying...'we have no land for our house.' For this we need citizenship, but it is not with us."

Ethnicity and language form the basis for defining Nepalese national identity, which is significantly skewed in favor of the Nepali-speaking castes. These distinctions have also been used to cast doubt on the origin and nationality of millions of people in the Terai, and reinforce claims that they are originally from India. By 2007, an estimated four million people in Nepal were without Nepalese citizenship, including large numbers of people from the Dalit community.

Among the people of the Terai, the Dalit have suffered most. Deep-rooted discrimination has always left Dalit or “untouchables” throughout Nepal disadvantaged. Social stigma and poverty are inherited from one generation to the next. Dalit have been excluded from microfinance and economic development programs. They cannot own land and do not have equal access to basic social benefits. Unrecognized as citizens, they are unable to have marriages legalized or obtain birth certificates. Illiteracy rates among Dalit in the Terai, mostly among women and girls, are some of the highest in the country. Over two million Nepali work outside the country as foreign laborers, yet stateless Dalit cannot acquire passports and travel abroad. As others send money back to their families and communities, Dalit live in a painful reality where these opportunities are out of reach. Though the natural resources of the Terai fuel Nepal’s economy, most Dalit in the Terai feel condemned to live a hand-to-mouth existence.

“People in power are building a new Nepal. But officials say, ‘Why do you need citizenship? We give you jobs. We give you food. We give you everything you need to exist.’”

After the pro-democracy movement and the overthrow of Nepal’s monarchy in 2006, a short-lived citizenship campaign was launched across Nepal in early 2007. Over two and a half million people were issued Nepalese citizenship, yet many of the poorest and most vulnerable in the Terai found themselves excluded. Remote villages were too far away, administrative requirements were too complicated, and harassment and discrimination from registration officials made it nearly impossible for hundreds of thousands to obtain citizenship.

Today, interpretation of Nepalese citizenship law is commonly left to the discretion of local- and district-level bureaucrats and civil servants, most of whom are men from the Hill-caste majority. In addition, gender discrimination in Nepal’s citizenship laws continues to deny women the right to pass their citizenship on to their children. Recent estimates claim several million people continue to live in the country without Nepalese citizenship, including hundreds of thousands of Dalit men, women and children in the Terai.