MYANMAR (BURMA)

EXILED TO NOWHERE

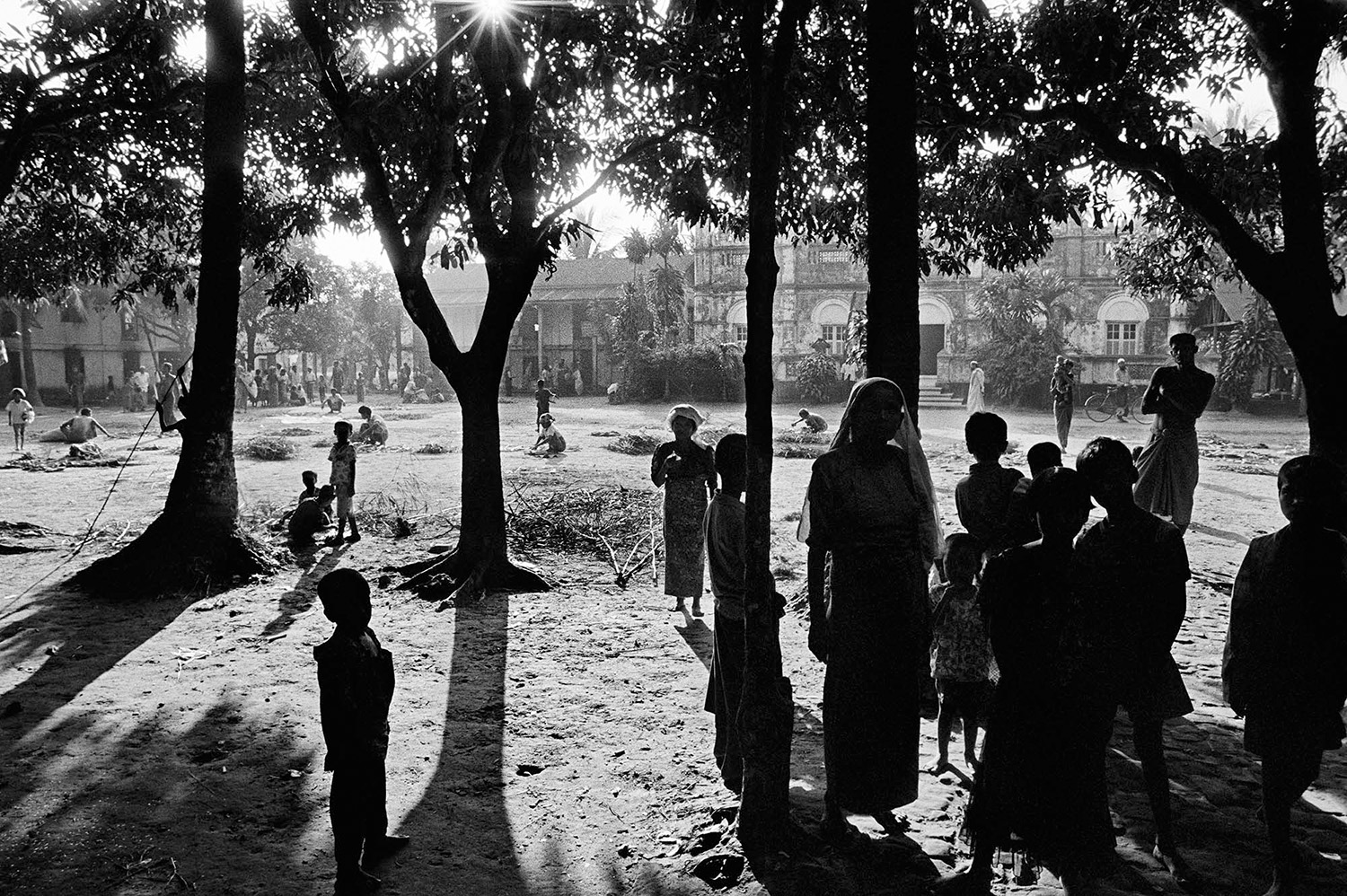

“This is the spot where my family’s house used to be,” twenty-three-year-old Mohammed says. Broken slabs of concrete from homes that no longer exist are scattered here and there. Two streets away, Burmese police sit behind barbed wire gates. They guard the entry and exit points to the Aung Mingalar neighborhood of Sittwe in Myanmar (or Burma). Inside the gates of Aung Mingalar, Mohammed and some five-thousand Muslim Rohingya are trapped in a modern-day ghetto, segregated from the rest of the city, unable to leave to work or go to school. Outside the ghetto, life continues. Bicycles, trishaws and motorbikes pass by the gates. Across the street restaurants are filled with chatty students from the local Buddhist Rakhine community. It has been several months since Mohammed’s home was destroyed by a Buddhist mob as Burmese authorities stood by and watched, but he feels the loss from those days of terror every day. “All Rohingya families used to live here,” he continues. “I don’t like to come here because my brother was killed in the violence. There is nothing left now. Now most are living in the camps.”

“Rohingya people who are living in Myanmar don’t have rights. Even a bird has rights. A bird can build a nest, give birth, bring food to their children and raise them until they are ready to fly. We don’t have basic rights like this.”

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority from the Rakhine State in western Burma, historically known as Arakan. Though the Rohingya trace their history in Arakan back for centuries, the government and local groups claim the Rohingya are originally from Bangladesh. Over the past fifty years, the Burmese government has refused to recognize the Rohingya. Burma’s 1982 Citizenship Law extends citizenship to people from 135 ethnic groups in the country. The list omits the Rohingya, a minority of over one million strong, arbitrarily depriving them of nationality and leaving them stateless in their own country.

"Since we don't have nationality in Burma we can't live in peace. In Burma they say we are from Bangladesh. When we come to Bangladesh, they say we are from Burma. People view us as if we don't exist."

In Burma, the Rohingya are subjected to religious persecution, forced labor, heavy taxation and extortion as well as arbitrary land seizure. Their daily lives have been paralyzed by discriminatory laws and administrative measures imposed specifically upon them. They cannot travel freely, require permission from the authorities to get married or start a family and are allowed only a restricted number of children. Over the past thirty years, hundreds of thousands have fled their homeland. Most are not recognized as refugees and are vulnerable to exploitation, human trafficking and other human rights abuses.

"...Because we don't have citizenship, we are like a fish out of water, flapping and unable to breathe. If we were given citizenship in Burma, we would be like that fish you catch and then throw back into the water where he belongs. We are still out of water and when a fish is out of water, he suffocates to death. We have been out of water for such a long time and we are suffocating. We are suffocating to death."

"My house in Nazir was completely burned down. The Rakhine threw petrol on it while the security forces aimed guns at us. We left with our lives. We are not allowed to take anything from the house."

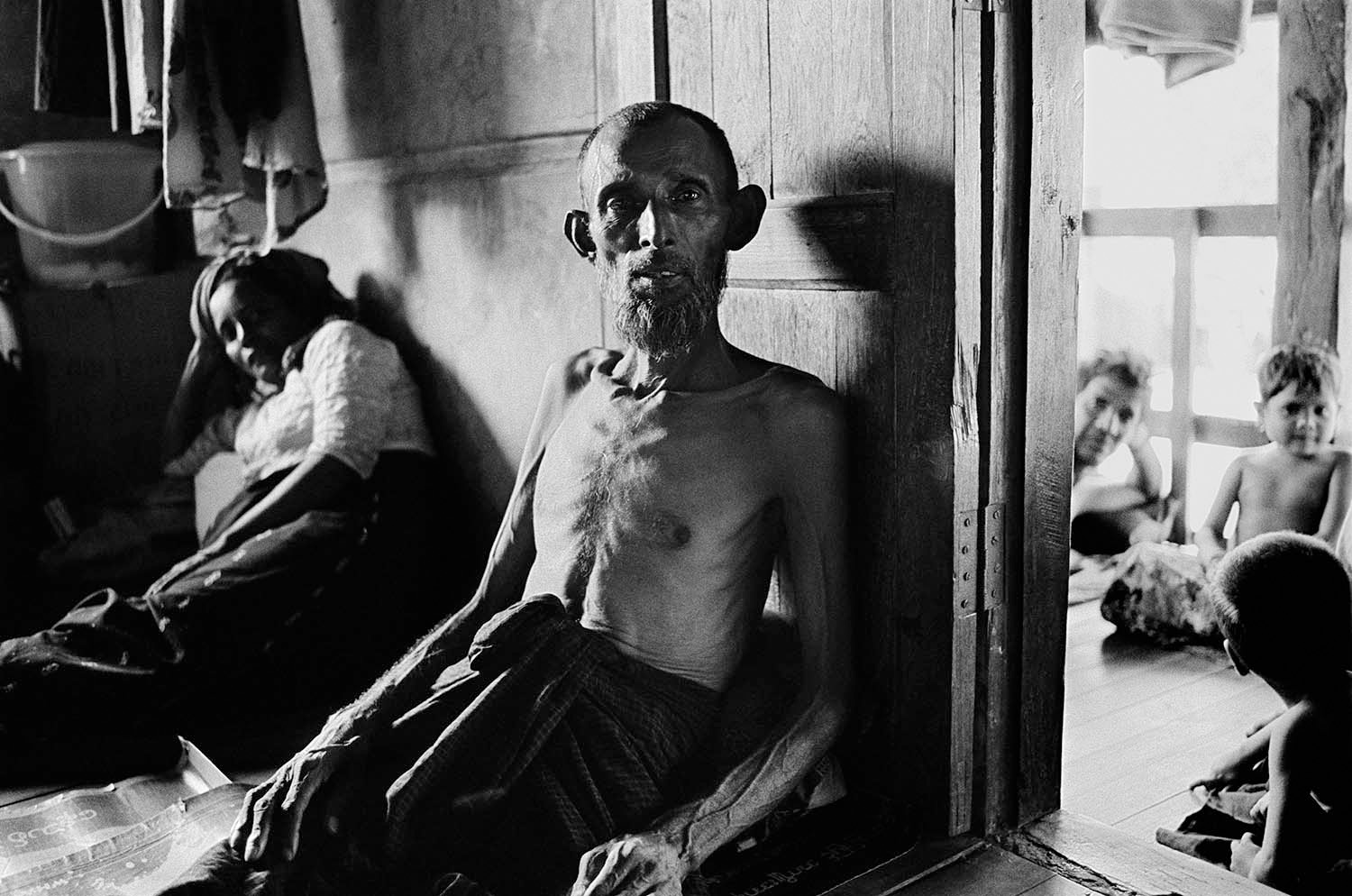

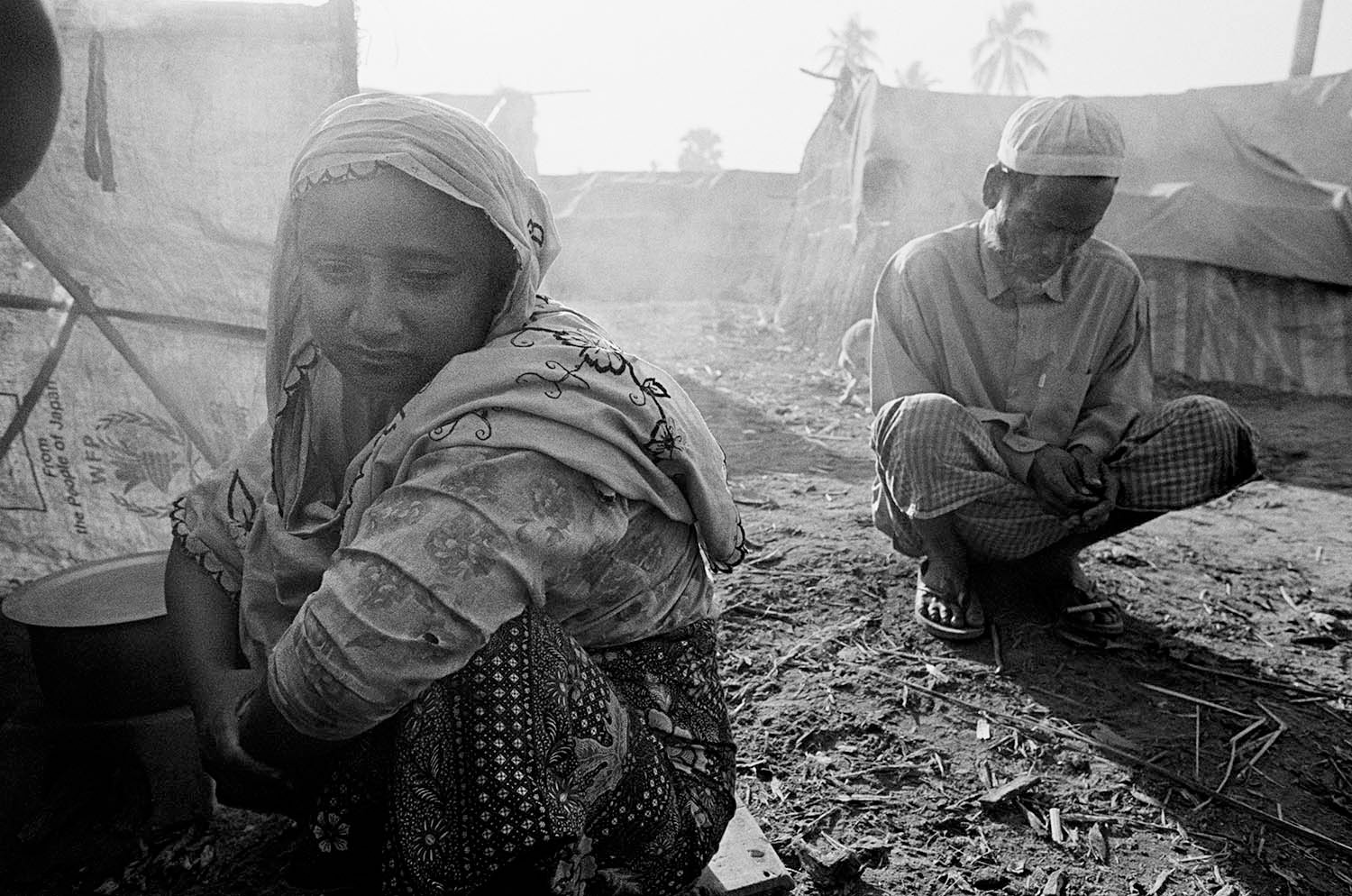

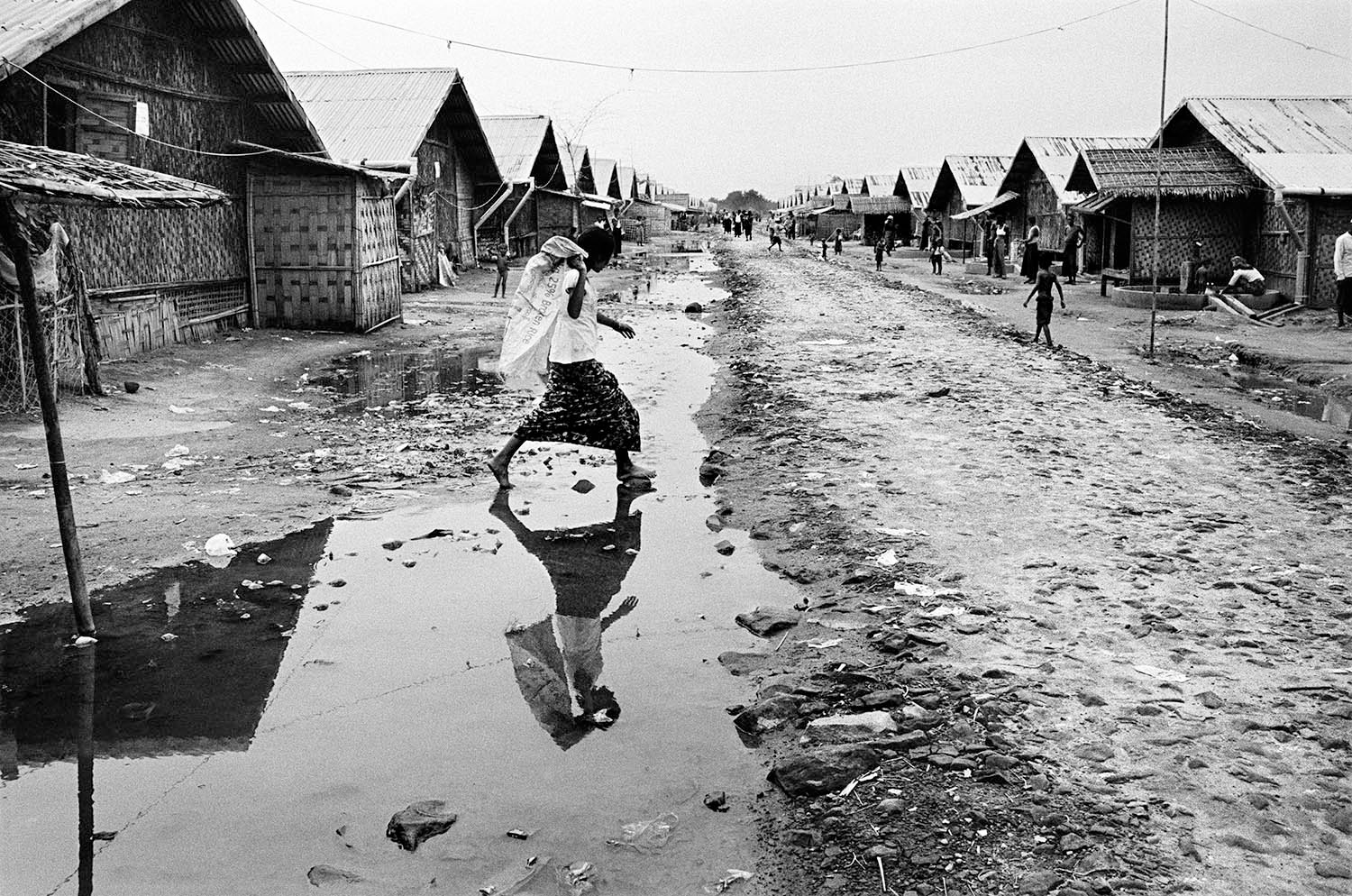

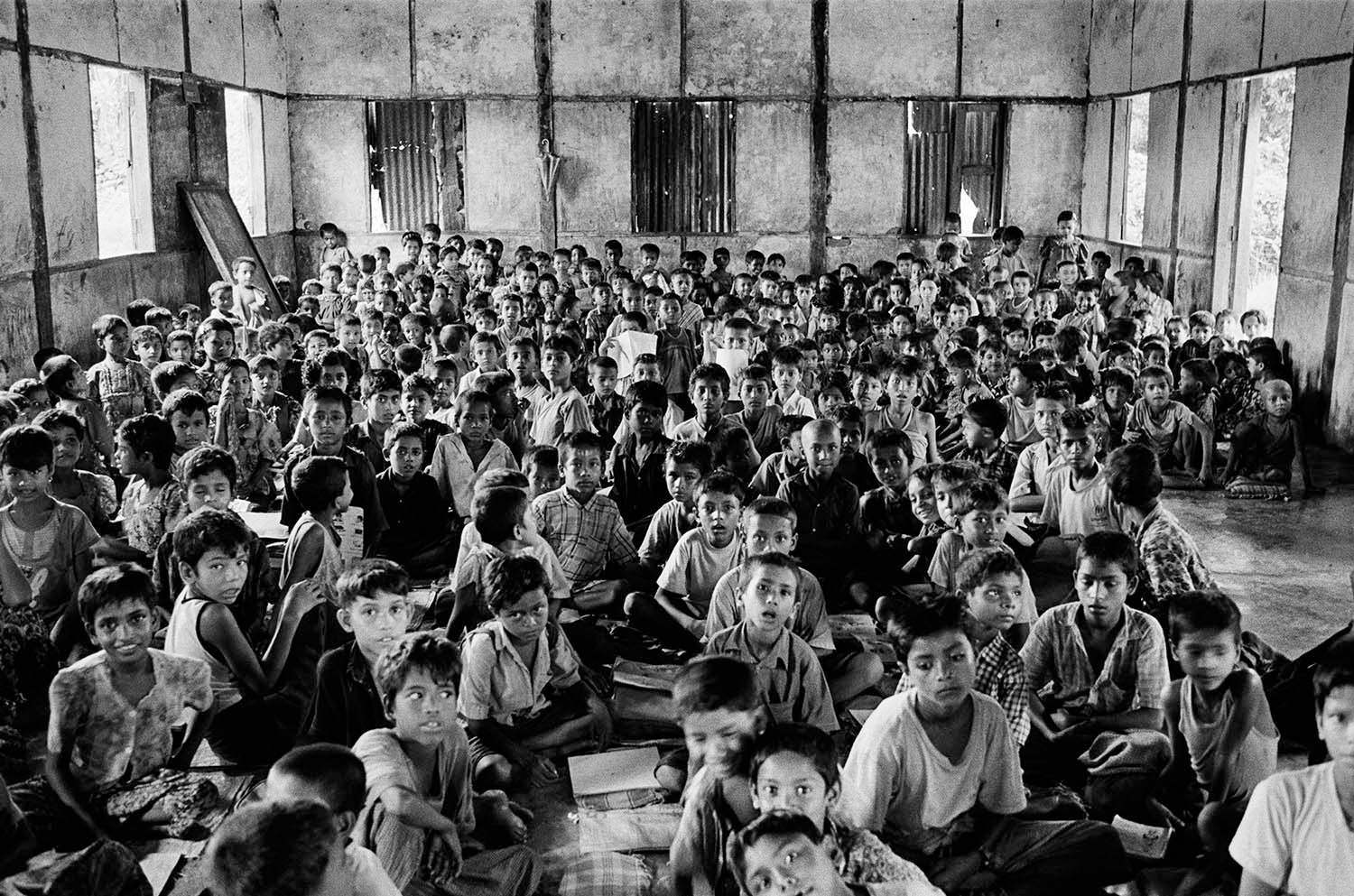

In 2012, violence erupted between the Rohingya and Rakhine communities. The violence essentially erased the entire Rohingya community from Sittwe. Throughout Rakhine, Rohingya villages and neighborhoods were leveled to the ground. Businesses and property were confiscated. Over one hundred forty thousand Rohingya were displaced and forced to live an apartheid-like existence in isolated internment camps for internally displaced people (IDP). In the camps, they cannot leave, go to school or receive proper medical care and are dependent on international humanitarian assistance.

Burma’s transition toward democracy has created space for new political voices. By promoting religious intolerance, racism and hatred toward the Rohingya, ultra-nationalist Buddhist monks and Rakhine political parties have advanced their own agendas for how Burma should define its national identity. Both groups refuse to acknowledge the existence of a community called the “Rohingya”. Authorities insist that they must first identify themselves as “Bengali” before any consideration is given to their citizenship. In 2014, they were excluded from Burma’s first census in thirty years, and in 2015, authorities revoked their temporary ID cards. Some human rights groups have described the ongoing abuse as ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, and the international community has condemned the situation. Regardless, leaders inside the country have shown almost no political will to temper the fervor or recognize the Rohingya. This has perpetuated the legacy of abuse that has plagued them for over fifty years.

"These three miles where all the of the Rohingya live is like a three-mile jail."

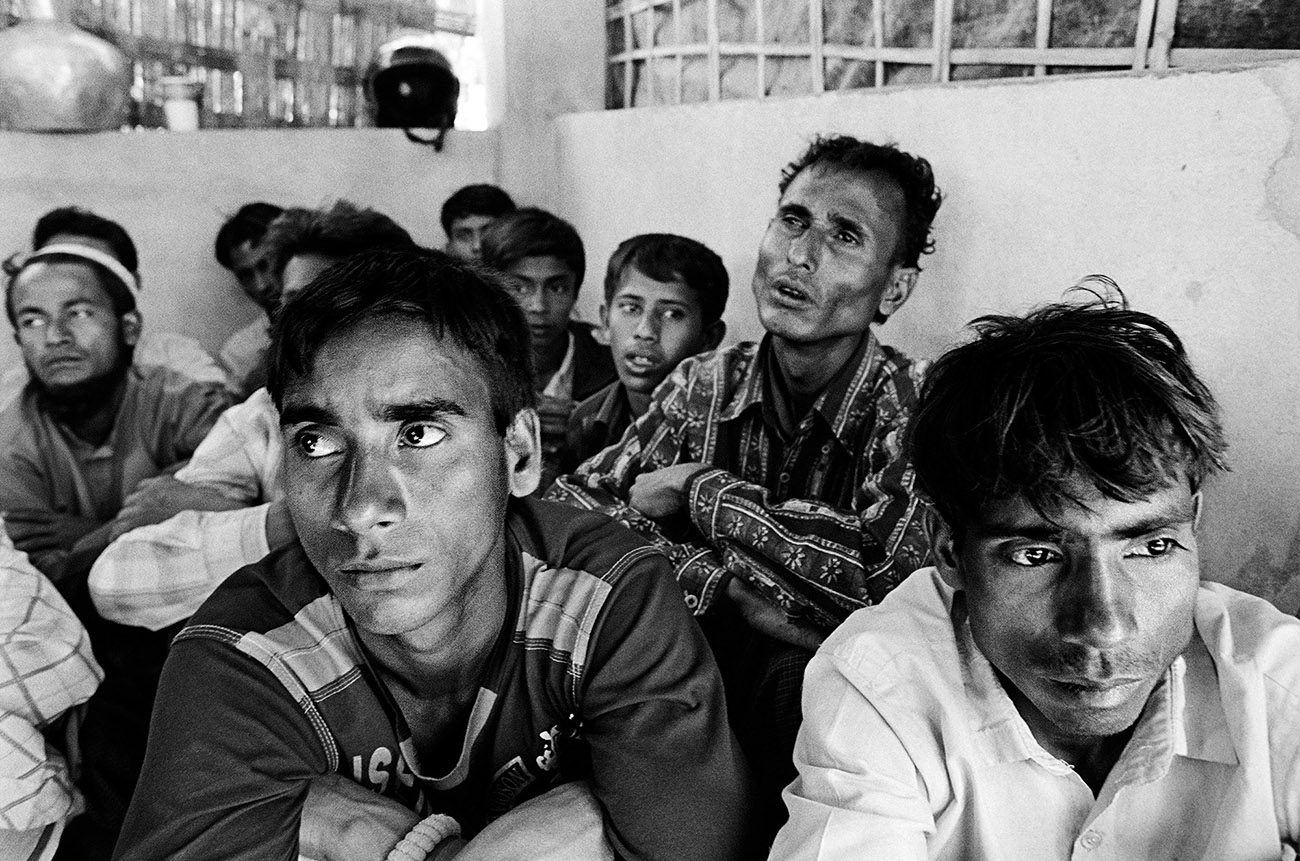

Each year, thousands of Rohingya pay brokers to smuggle them by boat from Burma and Bangladesh to Malaysia, Thailand and beyond. Recently, thousands of Rohingya have been delivered into the hands of human traffickers in Thailand and Malaysia where they are imprisoned in jungle camps, sold into slavery or simply disappear. Desperate and increasingly at risk of more violence, the Rohingya forge ahead despite the rocky ground beneath their feet. They suffer the abuse in Burma but endure. They flee to other countries and adapt. They place themselves at great risk for their families, determined to see their lives are not ruined.

"There is no life to live here so he went to find a better one. He got on a boat two months ago. Now we don't know where he is. What are his wife and daughters going to do now?"

Walls of plastic sheeting inhale and exhale as the wind shifts directions around thirty-year-old Monzur’s makeshift hut in southern Bangladesh. He sits wearing a dark green Burmese longyi with his legs crossed. He explains how recently there seemed to be no end to the abuse he and the other Rohingya in Burma were subjected to on a daily basis. He fled from Burma earlier that year, crossing the Naf River, not knowing what to expect. Sitting among the filth, sickness and desperation of his new life in Bangladesh, he still says it is better to be here than back home. Yet reality is sinking in and sadness has settled in his eyes: he is a stateless refugee, living in subhuman conditions, with little hope of returning to his home. “God created many species and every species has a place to live,” Monzur says. “Ants and snakes have a hole. Fish have the water. Tigers and bears have bushes. But Rohingya don’t have anyplace to live. We want to ask the world, where is our place?”